Salt, Storms, and Seafood Await in This Stretch of Pacific Northwest Coast

Ocean waves echo into everyone’s business here.

The king tides pour into Netarts Bay in winter, forcing the Jacobsen Salt Company to pause pulling water out. It’s all part of the rhythm here on the Oregon coast, where so many local, small-batch businesses pause for nature to do its thing. And it’s easy to see why shops and people have been tempted by this parcel of land. Even through massive sheets of rain, the serenity of a quiet coast here in Tillamook county comes through: seemingly endless horizons of misty, pine-topped cliffs and honor-system farm stands offering eggs, U-pick oysters, and bags of foraged chanterelle mushrooms stapled to A-frame signs.

Though Tillamook shares a landscape with the tourist towns just an hour north—Cannon Beach, Seaside, Astoria—this region attracts about half the visitors. But its fierce waterways irrigate an ecosystem of unique creators and producers that make the Tillamook Coast an inspiring place to explore—even when the tumultuous deluge falls so hard that driving becomes an experience itself.

But keep driving, hugging Whiskey Creek Road as it skirts the mile wide waterway hemmed in by Cape Lookout State Park. The craggy rocks sticking up from the water and jagged cliffs looming over long beaches hardly give an impression of blank space waiting to be filled. But it clearly offers the room for people to set up something quintessentially their own and gives visitors a chance to explore those tiny, personal niches.

From a red seaweed grower to a boat museum offering seafood cooking classes, here are all the places along Oregon’s Tillamook Coast that will make you relish weathering the rainstorms.

Find food flavored by the ocean

“This is not Downtown Portland,” says Todd Perman, the founder and owner of JAndy Oysters. Like Jacobsen, which uses water from Netarts to make its fancy salt, Perman takes advantage of the 99% salinity and clean water to let nature flavor his products. He harvests shellfish daily to sell to restaurants and distributors, and now serves them at his oyster bar in Tillamook, 20 minutes inland.

“There was no place in Tillamook to get raw oysters and a beer,” he noticed, despite the many growers in the nearby bay. So three years ago, he pulled the boat out of his warehouse, bought a keg, and started handing out free beers to people who came by to pick up shellfish or linger for freshly shucked oysters. “The goal was fresh seafood for an affordable price,” he continues, something helped by the impromptu location and lack of a liquor license.

It recently outgrew the garage, moving to a larger location in an old garden center and became a legit business (that now charges for the beer). But Perman is quick to remind visitors of his origins. “I’m just a farmer,” repeats the 30-year-veteran of the logging industry. He started JAndy, named for his son, Jacob Andrew, a decade ago, and thrived on the change. “I came from an industry where everyone hates you,” he says. “Farming in Netarts, everybody loves you.”

Others have simpler reasons for coming to this quiet coast. “It was cheap,” says Naveen Malhotra, who owns Bayside Market and Deli with his wife Nidhi. They previously owned markets elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest, but now they sell sand shrimp for crab bait, deli sandwiches, and chicken curry in the tiny town of Netarts.

The big orange building stands out through the grayness of clouds, ocean, and cement, as bright as the turmeric-tinged curry, equally cozy with scents of coriander, and both with soul-restoring warmth on a stormy day. The crisp shell of the samosa shatters to reveal tender meat and potatoes, bolstered by garlicky green chutney. It goes against my instincts to buy anything but seafood when I could roll a stone down Crab Avenue and land it in the ocean, but eating it in my car as torrents of water create a rhythmic soundtrack on the roof, the steamy dish feels essential.

Half-an-hour north in Nehalem is Buttercup Ice Cream and Chowders. After ordering at the counter, I zig-zag through old toys and dog-eared books in an antique store to get to the covered and heated outdoor patio, where I watch the town’s eponymous river rise as I sip a chowder made of local razor clams. Herby and light, it tastes of the salty air that puffed out of the boiling cast-iron vats I visited at Jacobson and feels like the antidote to the dampness that seems to emanate from the streets.

Meet producers who forage from the sea

On the edge of Tillamook Bay, Alanna Kieffer finds a warm welcome from the region—once curious passersby figure out what it is she’s offering. Inside the dulse farm she manages for Oregon Seaweed, twenty enormous tanks circulate seawater around curly red algae, letting it bask in the sun and absorb nutrients. "We should get a sign," she muses as she wanders over and explains what we’re seeing here: a completely sustainable aquaculture operation that requires little more resource than the energy to pump the water in from the ocean a dozen feet away. Here, they grow the salty sea green that slides easily into stir-fries or crisps up like chips in an air-fryer.

Kieffer, a marine biologist by training, moved home to the area at the beginning of the pandemic and heard about the operation. But much of her job involves explaining to people what it is and how it grows so well in Garibaldi.

"It’s not that there’s not a demand for local food. It’s just getting it from point A to point B."

That’s a lot of what seafood procurer Kristen Penner’s work includes, too: figuring out how these uniquely special local food products could make their way into more local restaurants and find outlets further afield. “We’ve been really accustomed to just getting food that’s easy to prepare off the shelf, and not really seeking out the things that are very local or regional specialties.” Her one-boat fishing operation sells fresh catch directly to shops and restaurants. She hopes to make it easier for people in or visiting the Tillamook Coast to do that. “It’s not that there’s not a demand for local food,” she says. “It’s just getting it from point A to point B, there’s so many steps in the process.”

The Salmonberry, a restaurant in the town of Wheeler, does the best job so far: it serves the same local Wolfmoon wild yeasted sourdough bread as Buttercup does with its chowder, and JAndy’s Netarts Sweetheart oysters come with a red dulse mignonette from Kieffer’s seaweed. My experiences trekking across the salty bay all come together in one rich bite.

Explore old boat lore

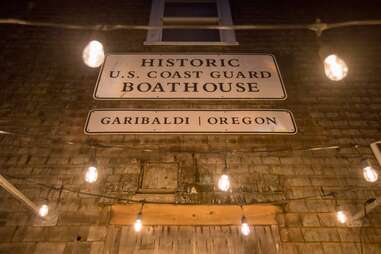

Penner has her own pet project, too: the Garibaldi Boathouse, a museum that capitalizes on the location by offering experiences like boatbuilding and seafood cooking classes. It’s situated in an old 1936 Coast Guard rescue station, perched over the Pacific.

To get there, visitors walk 750 feet along the pier that stretches out over—depending on the time of day—either the tideflats or waves, passing multiple generations of families tucked into the wooden crabbing turnouts, hoping to catch dinner. After ducking through the gauntlet of sea birds posing on posts, threatening to divebomb those who pass before flying away, you reach the building.

The Coast Guard decommissioned the building in 1980, giving the Port of Garibaldi what turned out to be more burden than boon: It lacked easy access for use as a marina or a residence and fell into disrepair. In 2015, Penner led a group of locals in forming a non-profit and secured grants to upgrade the building, turning it into a historic site.

Hand-built kayaks hang from the ceiling, and white paint from the recent remodel give it a Nantucket feel. But the history of this scrappy stretch of the Oregon shoreline—quite literally written on the walls via archival photos and articles—prevents any glossing over of the ferocity of the area’s environment and inhabitants. The many stories told here include the luxury resort Bayocean falling into the sea in the 1930s, and the dramatic rescues launched for doomed fishing boats trying to snake through the dangerous entrance to Tillamook Bay.

Let waves lull you to sleep

When the storm clears and the tide recedes, the time is ripe for a walk along Oceanside Beach. Only a few other people dot the seven miles of beach: a family searching tidepools for interesting sea creatures, two teenagers crawling nefariously into a cave on the side of a cliff, and an elderly couple, bundled against the wind as they walk their small, fluffy dog. The wind and the waves provide a constant white noise, loud enough to drown out conversation, but not thoughts. They dominate the soundscape the same way the towering sea stacks steal the show from the rest of the scenery, the enormous rocks rising from the shallows like the long, chubby fingers of a submarine giant.

The hotel across the street, the Three Arch Inn, is a “self-service” facility, adding to the feeling of nature so big it crowds out other people: it’s unlikely to run into other guests here, nobody watches from the front desk as I come and go. Rooms have their own kitchen, where I bring in takeout from a taco shop in Netarts that's inside a general store and shares space with the Post Office. It's just me, staring out the enormous picture windows over the wide water as the invisible sun, hidden among the clouds, presumably sets and the night darkens.

My city girl instincts curl up in my suitcase and thoughts expand into the wide-open space—the same space that gives people like Penner, Keiffer, Perman, and Malhotra room to put down their own dreams, to put their own spins on the standard narratives. It’s a space that also provides a home for unique events, like the best excuse I've ever seen for a return trip: watching the local crabs race down chutes like tiny crustacean thoroughbreds.